The Homestead Act of 1862 was a U.S. law that allowed any adult citizen, or intended citizen, to claim 160 acres of federal land for a small fee, with the requirement to live on the land, build a home, and farm it for five years before receiving ownership. The Dakota Territory was divided into North and South in 1889, and State officials wanted to attract settlers. They spread pamphlets and newspaper stories that painted a wonderful picture of North Dakota. They sold the idea that the land was like a garden, and free is the best price.

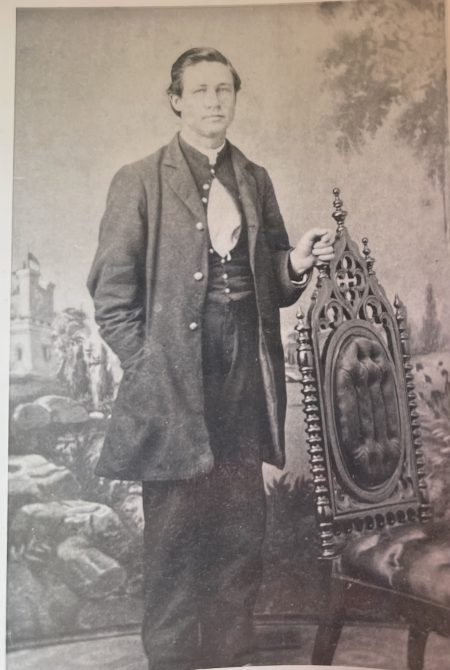

That must have appealed to the old soldier, Robert Horatio Walker. He had started out living with his parents in the house he was born in, working as a sawyer to feed the family. When George McWilliams died in 1881, he and the family had moved in with Catherine, and were farming. He and his cousins were well-respected citizens, hard-working and devout. But during his years in the regular army, fighting in the “Indian Wars”, he had no doubt glimpsed the spectacular. wide-open landscape of the Northern Prairies. All those years, he schemed to return. A born leader, he pulled together his children, his siblings, and his cousins and they began to plan their move.

They were nearly set to go in 1898, when Alexander Kinkade died suddenly in April. He and his brothers, Robert and Charles, were part of the group and the loss hit the family hard. Just as they were recovering, their mother, Robert Horatio’s aunt, and my 3x great-grandmother, Mary Ann Walker Kinkade passed away in September, at the venerable age of 80. She, too, may have been planning to move.

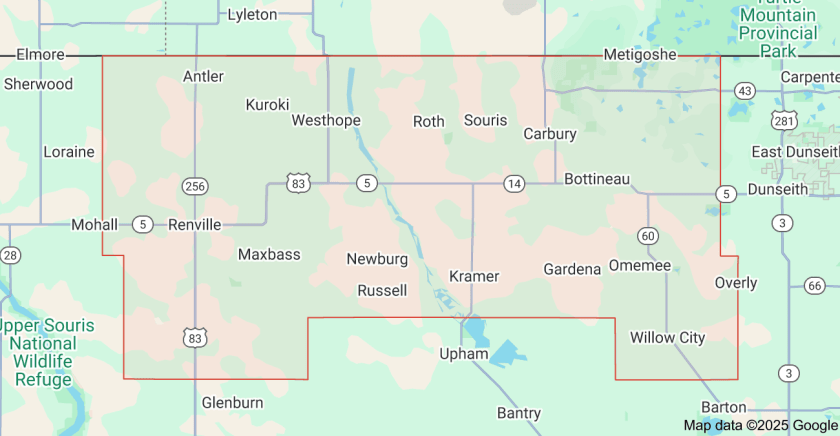

These developments slowed them down, but by 1899, the band of pioneers set off: Robert Walker, his two sons, Clyde and Ralph, son-in-law, Madison Wehrly, brothers, Joseph and William Walker, brother-in-laws, William Carothers and William Elliott, nephews, Arthur and Harry Pixley, nephew-in-law, Marion Barnhart, and cousins, Charley and Robert Kinkade, traveled to Sherman Township, Bottineau County, North Dakota.

Bottineau County, ND, is at the very tip-top of the state, along the Canadian border, near the Turtle Mountains. This part of North Dakota was fertile prairie and known for growing wheat. Westhope was the nearest train depot, about 10 miles from their homesteads, which were nearer Antler.

Each of the men filed homestead papers in Westhope for parcels in Sherman Township. Returning to Illinois for the winter, it was Spring of 1900, when they brought back machinery, household goods, and livestock. They built a sod shack that had one big room with curtains to divide it into separate rooms and the thirteen men worked out of that throughout 1900-1901.

These guys were no spring chickens…well, some of them were, but this was some rough living in a place known for its below-zero temperatures in the winter.

By the Spring of 1901, every family had a house. Down in Illinois, the McWilliams Farm, along with the Walker property, was sold, most of the Kinkade acres were sold, and the rest of the clan moved in by that Fall, including Robert’s mother, Abigail Reed Walker,73, and Maggie’s mother, Catherine Morrison McWilliams, 84.

Back in Richland County, IL, that Spring, Cousin Julia Walker Pixley and Aunt Hattie Kinkade Hall (and their husbands), both living in West Salem, IL, were all who were left of my great-Grandmother’s family. Her Uncle Bob and Aunt Maggie had urged her to come along with them, but Ollie Kate Kinkade (who had changed her name to Kathleen in 1898) had opted to continue living with Aunt Hattie and teaching music.

It’s a Good Thing that she stayed behind or I wouldn’t be here to tell their story. On April 16, 1901, while the pioneers were moving into their new houses, she married my great-grandad, Ben L. Mayne.

It was around 1995 when I mentioned to my grandaunt Bernie, 92 at the time, that her mother’s family was very small. She then told me a story her mother had told her, best she could recollect, that my great-grandmother had a very large, close family, but they had all “up and left”, gone “somewhere out west”. She had heard stories from her mother regarding her Aunt Maggie, and remembered meeting her granduncles, Charley and Robert Kinkade. It was decades later, after seeing the picture, that I was able to put the story together with Uncle Bob Walker.

And what happened to Robert Horatio and his band of Pioneers?

Stay tuned…